Author: Leónidas Neftalí González Campos

Sep 17, 2025

The Web is bad, but no one is willing to change it (yet)

A reflection on the current state of web technologies

When I was a child, I was fascinated by the tech world because I did not know how anything worked, the internet seemed like a never ending fountain of knowledge that was carefully crafted by experts, now… well, I am still fascinated, but now it is at the fact that everything is still somehow standing with so many layers of poorly constructed software architecture and needless overcomplicated abstractions; so, how did we get here, is there anything we can possibly do to make the web better, and most importantly, what does better even mean?

Table Of Contents

- So, what exactly is bad about it?

- What are the alternatives?

- How to build the BETTER web

- The ACTUAL issues with moving to WASM

- Conclusion… doing our part to build the new web

So, what exactly is bad about it?

Talking with friends involved in web development I often end up mentioning how I’m not particularly fond of the current state of their industry, and quite frequently I’m met with the same line of reasoning, “but why is this bad”, “it works fine dude”, “you’re just too tryhard”, this usually happens after bringing up emergent alternative technology stacks like WebAssembly and how it is so cool that I can now write straight C code that compiles to an actual executable the web browser will run, and I guess the assumption is that I want everyone to reimplement every single website in C and dump JS in the trash.

Or even better, just rewrite it in Rust!

That is not (entirely) true, there is a limit to how many wheels I’m personally willing to reinvent just to show a simple website, however, I am still critical of the chokehold under which JS has the whole industry on, it is truly a monopoly out there when it comes to picking how you’re going to build your apps, and it affects not only the developers (with an overflow of the job market and stale career growth), but the end user as well with every single site looking exactly like all the others, and not to mention the performance implications of both the language and poor engineering decisions… “Oops, sorry this took 10 seconds to load, we tested this on our intern’s MacBook Pro M4 Ultra, you should really reconsider using our product if you don’t have the minimum requirements”.

We have to remember that JS was not originally planned to be the absolute dephormed monster of a language that it is today, even getting to the point that we want to use it for everything

- You want a frontend? Javascript! How else are you gonna write React?

- Need a backend? Javascript! Node will take care of the heavy lifting

- Desktop apps? Javascript! Let’s just package a whole browser with that bad boy and you’ll be right at home with the same UI libraries

- Embedded systems? BELIEVE IT OR NOT, ALSO JAVASCRIPT!!!

it was fine as a scripting language, meant for simple DOM manipulation. That should’ve been it, another language could’ve emerged and solved JS’s issues, but, we decided to grab the spoon glue together a few spikes at the end and called it a fork, dragging along layers of complex frameworks. Could we simplify this paradigm without switching languages? Absolutely, imagine each codebase with its own lightweight, declarative UI library, tailored to its needs, something that you learn in one or two days along with your coworkers and banging your head against the code. From my experience there exists this strange attitude towards doing things that way, and it’s almost always along the lines of: “Duude, writing every UI component from scratch?? That’s way too hard!” But it’s not. Custom libraries can be lean and intuitive, cutting out the bloat of modern frameworks. I’m not saying this is the ultimate fix, far from it. It’s just a step toward ditching overengineered abstractions for something more purposeful and self-contained. Here’s a quick example to prove it’s doable: a simple button, built without the usual framework overhead.

// Declarative style properties and composition-based functionality

// You can fit as many events and properties as you like here

// And even define a couple constant ones if you want to, we just solved CSS

type ButtonArgs = {

backgroundColor: string;

onHoverColor: string;

textColor: string;

borderRadiusPx: number

onClickEvent: (args: any) => void;

};

function makeButton(text: string, buttonArgs: ButtonArgs) {

const button = document.createElement("button");

// CSS styles are already quite declarative, just use them!

button.textContent = text;

button.style.backgroundColor = buttonArgs.backgroundColor;

button.style.borderRadius = `${buttonArgs.borderRadiusPx}px`;

button.style.color = buttonArgs.textColor;

// No crazy complicated hooks or whatever the kids do atm

button.addEventListener("click", buttonArgs.onClickEvent);

button.addEventListener("mouseover", () => {

button.style.backgroundColor = buttonArgs.onHoverColor;

});

button.addEventListener("mouseleave", () => {

button.style.backgroundColor = buttonArgs.backgroundColor;

})

return button;

}

There you go! It really wasn’t that complicated, took me a total of 5 minutes of mostly looking up style properties and mapping them to the correct properties of our custom type, and here, you can even play around with it:

Clicked: 0 times

The button example shows a simpler way to build web UIs, straightforward, no bloat, just pure JavaScript manipulating the DOM (like god intended), I’d take this over modern web frameworks any day if not simply because it cuts all the dependency hell that we are forced to live in, relying on someone else’s code to do this (frankly) very simple stuff seems like a red flag, specially when the trade off for this is potential security concerns (at the time of writing this, there have been 3 separate consecutive supply chain attacks to npm packages within THE SAME WEEK).

By writing your own declarative components, you cut the middleman and reduce security risks. It is absolutely not the perfect solution, it’s a step in the right direction. Let’s break down why it’s not enough and explore a better paradigm: immediate mode UIs.

The problem with our button approach is that there is more boilerplate involved, we need to keep a reference to the created button and create a function to manually update its values:

// This becomes our state tracking function, which I'll admit, can be hard to keep track of

function updateButton(button: HTMLElement, buttonArgs: ButtonArgs) {

button.style.backgroundColor = buttonArgs.backgroundColor;

button.style.borderRadius = `${buttonArgs.borderRadiusPx}px`;

button.style.color = buttonArgs.textColor;

}

We then call this function every time you make a change to the buttonData variable… This is because the HTML -> JS UI interaction pipeline is a retained mode UI, and I think that THAT is the reason so many frontend frameworks seem so appealing to JS developers, as Reactive frameworks will try to emulate the feeling of immediate mode UI, but they need to jump through the hoops and limitations of the stablished HTML and JS interfaces to make it usable.

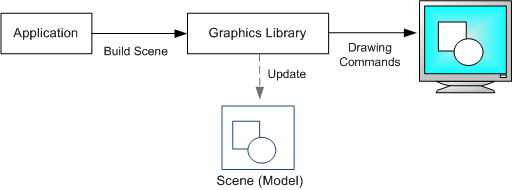

Retained mode, scene state is kept in memory and it's the "drawing" layer's responsibility to keep track of every component's change

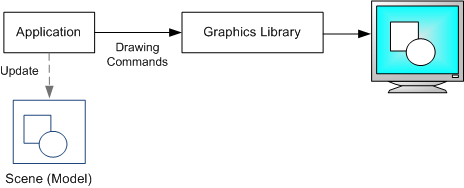

Immediate mode, scene state is never kept in memory and the state's responsibility falls to the "application" layer

This is exactly how you get things like useState, useEffect and the infamous re-renders, which are known to be slow, but here’s the thing… they’re only slow in this particular context, re-rendering everything is usually how graphical software is written, this is obvious for anyone who has ever done game development at some point in their lives, your engine/framework gives you a function that runs every single frame, and you recalculate your game’s state that frame, then the engine renders the result, in immediate mode, your UI is redrawn every frame, and every single variable is a state variable, it might sound counter intuitive, but this is actually a much more efficient approach to UIs than what HTML does on the background, because the rendering layer is no longer responsible of holding the state of your scene in memory, that becomes the responsibility of the application layer, and it’s also much easier for the programmer in my humble opinion, would you rather write this?

Simulated immediate mode counter component in React

export const Counter = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Click me!</button>

<p>Clicked {count} times</p>

</div>

)

}

Or this?

True immediate mode counter in C++ (DearImGui)

int count = 0;

void RenderButton() {

if (ImGui::Button("Click me!")) {

count++;

}

ImGui::Text("Clicked %d times", count);

}

For the first approach you have to:

- Be familiar with the concept of hooks

- Know what a stateful variable is

- Know how stateful variables impact the performance of your app

- Handle events

- Understand the JSX syntax

For the latter, you have to:

- Know what a variable is

- Understand if statements

- Optionally understand string formatting

I don’t know about you, but for all the talk JS gets about being a beginner-friendly programming language, React is doing it a disservice, and all for the sake of trying to use JS to do something it was not designed for… THAT is my thesis for this article, the fact that we introduce a shit ton of totally new issues and we’re willing to endure them before we even take a look at the alternatives we could be using instead.

The industry's attitude towards Javascript

What are the alternatives?

That sure was a lot of talk, but what about action, what can I use if not the “battle-tested” frameworks of the modern age? Well, there ARE options, but I’ll be the first to admit that they’re a bit rough around the edges (more on this later), WASM or WebAssembly is the core technology that will allow for essentially any application made in a language that can be compiled with an LLVM backend to run on the browser, as if it was a native app, this means, Zig, C, Rust, C#, and even Odin can produce fully featured web applications with as native a rendering as you can get, that is genuinely exciting, because, let’s face it, THE WEB IS THE UNIVERSAL VIRTUAL MACHINE we need to come to terms with this, no one is wasting precious hard drive space on whatever apps they might want to get, so your only way, as a business or product to get people to try your app is to have as frictionless a process for users to get their hands on it, and the web ended up being the dominant platform for this.

How to build the BETTER web

This far into the article you’re probably thinking: “Hey, isn’t this very site written in traditional JavaScript with React? It very much looks like it” And let me tell you… you’re absolutely right, don’t get me wrong, I truly believe every word I’ve written in this post, that includes the title “no one is willing to change it (yet)”, I gotta be honest, I tried to build this site using the technologies I just mentioned, C and WebAssembly, and honestly, I got pretty far, I was able to build headers, animations and containers, all things that I could personally never do in CSS and HTML, that is largely thanks to Nic Barker’s awesome Immediate UI layout library, Clay, I started to feel the real issues of using alternative technology stacks when certain small things did not quite work as you’d expect in the traditional frameworks, things like mouse scrolling, I am 100% sure it’s just a skill issue on my end, because the website for Clay is written in C and it looks REALLY NICE.

On my implementation, I don’t know why, but I couldn’t get the mouse scroll to work as smoothly as I wanted it to, and the lack of documentation and certainly a lack of patience on my side lead to my decision of abandoning that idea perhaps a bit prematurely, I plan on trying that again, don’t get me wrong, but, I JUST wanted to put my blog out there as quickly as possible, and this is a perfect reflection of the core issue at hand, companies don’t want a new experimental and bold tech stack, they don’t care about which language their landing page is written in, they care about shipping fast, and if sloppy carelessly crafted, dependency ridden and performance killing code will get them there faster, because of the larger work force pool they will absolutely choose that.

But I won’t shy away from showing what I tried to accomplish, here’s the page I tried to make (this is all just C++ code, but Clay also has bindings for other languages, like Odin):

Alright, it’s not a lot, I’ll admit it, but, without looking at the Clay documentation, purely off of the header file and my previous experience with UI libraries I was able to make:

- Header

- Buttons

- Some simple animations

- Flexbox layouts

all in a modular/component-based architecture with true immediate mode UI rendering, and it was honestly pretty fun too, it was above all else a refreshing experience, and even though I left it quite incomplete, I still learned a lot from it, and most importantly I DO SEE A PATH FORWARD FOR THIS APPROACH TO WEBDEV

The ACTUAL issues with moving to WASM

Let’s face it, the web and its technologies are pretty much set in stone now, everyone knows a website is made up of HTML, JS and CSS, and we’ve built a lot of technologies and tools under this assumption, so there ARE genuine concerns when someone claims they’re “just” gonna write it in WASM, let’s dig into them…

Accessibility

If we’re relying on RAW pixel rendering for everything in our websites, then, a “blog” such as this one might actually suffer from that choice, since people tend to use voice readers to navigate through them in an easier manner, not to mention visually impaired people, as I said, we’ve built tooling around the assumptions we have of the web, and if all webistes suddenly changed to WASM without having this tooling in mind, someone out there is suddenly going to get completely cut off from the web due to the lack of support for new technologies from the same tools; there might be a way to connect to the underlying reader / interactor API of the browser, but I am honestly not sure…

This is by far the biggest hurdle to clear to properly adopt WASM as a viable technology for user-friendly web applications, I do think that the technology is very new and there are things that we can improve upon / standardize, this is why I mentioned no one is willing to change the current state of the web, because adapting new technologies means slowing down, and that’s not something a profit-seeking company will want to do very often, as with many things in tech we have to rely in one of two things, either we get funding from a military-oriented application of these platforms, or we wait for a good samaritan to develop it and open source it to the world from the kindness of their heart. I am by no means someone qualified enough to set the next wave of web standards, but I believe pushing for the adoption of these new alternative approaches to webdev will yield innovation in the field from an industry that is desperately calling for it but being answered with a new JS meta-framework on a regular basis instead.

Conclusion… doing our part to build the new web

The bottom line is this, if the tech isn’t used, it won’t be developed further, so, the more we build with it, the more likely it is for good stuff to come out of it, libraries, utilities, tools, and full blown products, and thus, all following apps will get easier and easier to make. We can all contribute a small thing from many different areas, on my end, the visualizations on this very page are all written in lower level languages compiled with emscripten, up next here are some ideas off the top of my head:

For frontend developers

If you’re skilled in CSS, then you could focus on creating custom components for Nick Barker’s Clay layout library, we’re always going to be in need of spinners, progress bars, nice looking buttons, etc. distributing them should be extremely easy as a single header library. Clay is by design similar to a flexbox-based layout in CSS, here’s a simple button component in C++

using OnClickFunc_t = void(*)(Clay_ElementId elementId, Clay_PointerData pointerData, intptr_t userData);

struct ButtonArgs {

uint16_t fontSize = 24;

bool active = false;

OnClickFunc_t onClick = {};

intptr_t callbackArgs = 0;

uint16_t padding = 8;

Clay_Color bgIdleColor = ColorUtils::Transparent();

Clay_Color bgHoverColor = ColorUtils::Transparent();

Clay_Color fgIdleColor = ColorUtils::LightGray();

Clay_Color fgHoverColor = ColorUtils::White();

};

inline void RawButton(Clay_String buttonText, const ButtonArgs& args) {

CLAY({ .layout = { .padding = CLAY_PADDING_ALL(args.padding) }, .backgroundColor = Clay_Hovered() || args.active ? args.bgHoverColor : args.bgIdleColor}) {

CLAY_TEXT(buttonText, CLAY_TEXT_CONFIG(TextUtils::Default(args.fontSize, Clay_Hovered() || args.active ? fgHoverColor : fgIdleColor)));

Clay_OnHover(args.onClick, args.callbackArgs);

}

If you’re feeling bold, you can absolutely implement your own UI layout library entirely from scratch!

For tool developers

The development environment around native web applications is still young, so it’s a perfect oportunity if you like to innovate around what we use to make our apps, text-to-speech readers, HTML renderers, wasm embedders, HTML shell templates, or, even contributing to emscripten are a few ways that I can think of of improving the state of our tools so far!

Finally, for Backend developers

STOP USING JAVASCRIPT ON THE SERVER.