Author: Leónidas Neftalí González Campos

Nov 08, 2025

Everyone should learn C - Part #1: Error handling

A deep dive into what became the most impactful move in my carreer

Table of contents

Introduction

If you’re reading this, you’re either interested in learning C, or you’re somewhat skeptical on why YOU specifically should learn it, even if you’re on a field that rarely ever dips that low into the abstraction layers.

You’re probably thinking “Why should I bother learning a language I won’t ever use, I use Python/Java/C#/JS” or any other higher level language. My thesis here is that no matter what language you actually code in every day, learning C will fundamentally change how you think about computers and problem-solving, I’m confident on that because I myself have gone through this process where I thought I knew how to program, until I got thrown into a C project, and got tasked to add a value to a list… Oh, boy!

Throughout this series we will take a look at a simple piece of code and try to see what we can learn from it, the benefit of C is the fact that the language is extremely simple, it does not give you built-in data structures or fancy ways to impose rules on your typesystem, programming in C boils down to knowing that ANY program in the world can be made from 2 computer science primitives:

- Data

- Functions

And that lack of language features is what forces us to get creative to achieve complex behavior through simple constructs.

Demistifying C

It’s not C++

I think there’s this really weird sentiment towards C, people think it’s this incredibly hard language with indecipherable syntax, and scary pointers; to them I say, you’re thinking of C++, NOT C, at its core, the C language is probably the simplest lower level language out there, and that’s where its beauty and power lie. I won’t try to trick you either, this language has got issues, you gotta be aware of quite a lot of things when you program in it, and to be honest the type system leaves a lot to be desired, this is why most of my personal projects are coded in C++, but I try to minimize the features I use from that specific language, I generally keep it at constexpr (compile-time expressions) and template (generics) for a more robust type system.

C vs Python examples

To prove that C is indeed very simple and encourage you to get your feet wet a little bit, here is a simple program in C and Python that I bet you will find very easy to read, I will obviate the includes and those kinds of things because I really want to focus on the actual line by line instructions that we write, because I believe that will show that C truly is a lot more approachable than people think.

Read some names from a file and print them to stdout

#define MAX_LINE_LENGTH 256

FILE *file = fopen("names.txt", "r");

if (file == NULL) {

perror("Error opening file");

return;

}

char line[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

while (fgets(line, MAX_LINE_LENGTH, file) != NULL) {

printf("%s", line);

}

fclose(file);

And in Python (not using with here for ilustrative purposes)

file = open("names.txt", "r")

for line in file:

print(line, end="")

close(file)

Yes, there are more lines in the C version, that much is obvious, but I think the flow of information (WHICH IS WHAT WE PROGRAMMERS SHOULD CARE ABOUT) is essentially the same, one might argue, better in the C version, since error handling is not automatic, and we actually have a better grasp on our code structure there, not to mention, the C program performs only one memory allocation (the fopen call), it knows almost all the memory we will use every time at compile-time (before the program runs).

Now, there’s obviously a lot you can say here to argue for the python version, like, that same automatic error part, python handles that elegantly and right out of the box, that level of abstraction is really nice to have when you’re trying to put together a quick system to get the job done, but here’s the thing, I wholeheartedly believe that NOT having those abstractions makes you a better programmer, because of the hardships that those imply.

A muscle gets bigger by damaging it

Have you ever gone to the gym? Have you ever felt that burn on your biceps when doing curls and thought to yourself “Oh, yeah, I’ll be sore tomorrow, that means it’s working”, that feeling is your body telling you to stop what you’re doing, it’s uncomfortable and some might even say painful… but you push through the pain, why? Well, that’s a sign that you’re reaching its strength limit, and in response, your body will adapt and rebuild your muscle to expand this limit, so the next time you do a curl you can actually lift that weight with less effort. It was awful at the time, you stressed a muscle and it got bigger, stronger, THAT is what learning C does to you.

Let’s break down that file opening code, we can learn some very important lessons from it that can apply to almost all programming languages in error handling:

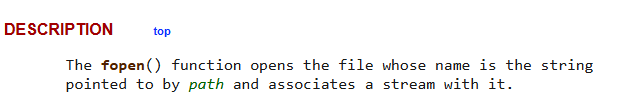

We can start by looking at the definition of the fopen function

This already tells us we should expect a FILE* that could be null, so it’s the caller’s responsibility to check its value before using it, a simple if guard should do the trick

FILE* file = fopen("names.txt", "r");

if (file == NULL) {

perror("There was an error trying to open the file!");

return;

}

// It is safe to use the file here:

This function teaches us to be careful of null or empty values, a concept that is essential for almost every programming language out there, we should always check the validity of a function call, since even simple things like allocating memory can technically fail if, for example, the system is running out of memory.

Now, this isn’t Go, so repeating if (res == null) {} over and over again can get really boring and tiresome really quickly, thankfully, C provides us with the tools to make it easier and adapt to these types of “defensive patterns” to either stop us dead in our tracks when something goes horribly wrong and the program can’t continue any further, or even handle the error elegantly and ignore it.

Defensive runtime check (elegantly ignore/handle the errors)

Let’s start with the latter approach, we want to catch errors and respond to them elegantly at any point of our application, so even if something fails, it fails in a deterministic manner, and we can decide how to move forward / notify the user.

This can be done with a simple if statement, just like we saw earlier, but, we’re fancy, so we can create a few simple macros that will take care of this operation automatically, keeping our code clean, readable and procedural.

A Macro in C is a simple copy-paste replacement operation where you define a function-like term that will be expanded to the full contents at compile time. for example

#define PRINT_VECTOR(vec) printf("(%.2f, %.2f, %.2f)\n", vec.x, vec.y, vec.z)defines a macro to print a 3D vector that when called like thisPRINT_VECTOR(playerPosition), the compiler will expand it to:printf("(%.2f, %.2f, %.2f)\n", playerPosition.x, playerPosition.y, playerPosition.z)

#define ERR_COND_FAIL(condition, retval) \

if (!(condition)) { \

return; \

}

#define ERR_COND_FAIL_V(condition, retval) \

if (!(condition)) { \

return retval; \

}

#define ERR_COND_FAIL_MSG(condition, format, ...) \

if (!(condition)) { \

fprintf(stderr, \

"Condition failed at %s line %s! " fmtFormat, \

__FILE__, __LINE__, ##__VA_ARGS__); \

return; \

}

#define ERR_COND_FAIL_MSG_V(condition, retval, format, ...) \

if (!(condition)) { \

fprintf(stderr, \

"Condition failed at %s line %s! " fmtFormat, \

__FILE__, __LINE__, ##__VA_ARGS__); \

return retval; \

}

Now, our code can look like this:

#define MAX_LINE_LENGTH 256

FILE *file = fopen("names.txt", "r");

ERR_COND_FAIL_MSG(file != NULL, "Error opening file!");

char line[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

while (fgets(line, MAX_LINE_LENGTH, file) != NULL) {

printf("%s", line);

}

fclose(file);

The error is still handled and the function is still easy to understand.

Errors as values

The lack of exceptions in the C programming language creates a need for proper error handling as simple value types, this technique is called errors as values and it is my personal favorite way to handle operations that could have one or many errors going into them, the idea behind this technique is simple, return a value (usually an enum member or an integer), and any results from the function can be stored in out pointers, let’s take a look at an example:

We are going to make a function to log in a user to our app, usually, the function would take in just the userName, password and it would return an actual instance of the User class with data from our database, it would like something like this:

User UserLogin(const char* userName, const char* passwordHash) {

DatabaseHandler database = DatabaseGetHandler();

// Pray we are connected to the database(?

int64_t userId = FindIdFromUserName(database, userName);

if (userId < 0) {

// Oops, user not found

return User{};

}

User result = GetUserFromDB(database, userId);

// We check the hashes are equal

if (strcmp(result.passwordHash, passwordHash) != 0) {

// Oops, incorrect password

return User{};

}

return result;

}

You can see we have several failure points along that function… A lot of things can go very wrong, and sure, we could learn to handle all those, after all, the function will return an empty user in case of any potential failure, but that does not tell us WHY the function failed, and that is crucial not just to catch errors in production, but also to make our code reliably testable and easier to debug. Let’s refactor that with errors as values

// We define a set of known errors that encompass the domain of our operations in a general sense

typedef enum EError {

Ok = 0,

EntryDoesNotExist,

IncorrectPassword,

FailedConnection

} EError;

// We no longer return the User value, we return the error value, and the user is now treated as an out reference parameter

EError UserLogin(const char* userName, const char* passwordHash, User* outUser) {

DatabaseHandler database{};

EError err = DatabaseGetHandler(&database); // We changed the database handler to use this technique as well

// We cascade the error return to the user login call (this way we have our little call stack trickle down to the earliest caller)

ERR_COND_FAIL_MSG_V(err != Ok, err, "Failed to connect to the database, errno: %d\n", err);

int64_t userId = FindIdFromUserName(database, userName);

ERR_COND_FAIL_V(userId >= 0, EntryDoesNotExist);

// We set the value of the out reference

*outUser = GetUserFromDB(database, userId);

bool passwordsMatch = strcmp(outUser->passwordHash, passwordHash) == 0;

// We check the hashes are equal

ERR_COND_FAIL_V(passwordsMatch, IncorrectPassword);

return Ok;

}

This method does not only handle its responsibility of logging the user in and validating that, but it also provides quite a lot of insight throuhgout its validation process for any caller to decide how to handle that error.

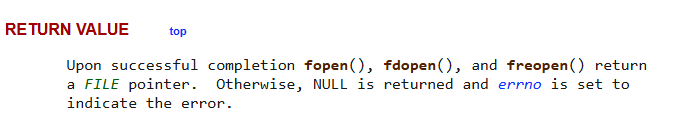

Errors as values in other languages

I could not possibly live without errors as values now, it has become the absolute default way for me to code anything, so much so that I made a small bootstrapper library to get me started on any backend work in C# WITH errors as values, it’s called Aspis.NET

The core of Aspis.NET is this enum and result types, which are our values for any possible general errors:

namespace AspisNet.Utils.ApiOperations {

/// <summary>

/// Possible results of any Logic operation (they should be used in a wrapper to return the proper status codes)

/// The API could return more than one of these in the form or a binary or operation, so check for <see cref="Enum.HasFlag(Enum)"/>

/// </summary>

[Flags]

public enum ApiOperationStatus : uint {

None = 0u,

Success = 1u,

Created = 2u,

Updated = 3u,

/// <summary>

/// The input of a process was not in the correct format

/// </summary>

ValidationError = 4u << 0,

/// <summary>

/// Tried to fetch data that does not exist in the Database

/// </summary>

EntityNotFoundError = 4u << 1,

/// <summary>

/// Tried to post data, but it currently exists in the Database

/// </summary>

DataConflictError = 4u << 2,

/// <summary>

/// A user tried to access a resource that they're not allowed to / they have incorrect credentials

/// </summary>

AuthorizationError = 4u << 3,

/// <summary>

/// Some behaviour internally in the program did not go as expected

/// </summary>

InternalError = 4u << 4,

UnkownError = 4u << 5,

IsErrorStatus = ValidationError | EntityNotFoundError | DataConflictError | AuthorizationError | InternalError | UnkownError

}

}

Usage of Errors as values in a C# API

Assertions

Assertions are the first option I mentioned, something horrible that shouldn’t ever happen just happened and our program SHOUL NOT continue execution because our assumptions about the state of the program are incorrect, so any code beyond that point cannot be reliably executed. This is an extremely useful tool in a development environment because it completely stops the program, and if you have a debugger attached it will automatically take you to the line where the assertion failed for you to debug right there and check what caused the state to be incorrect.

// Asserts are usually for dev-only checks, things that should not ever be left to the user

// So, our example here changed from loading a names file, to loading an internal resource, if this fails, the whole program is f*cked

FILE* file = fopen("app_config.conf");

assert(file != NULL);

// Use the file to setup the entire app's config here

Some codebases will even define their own asserts to hault the program, call the debugger and add some important context in the form of a message, here is an example from my own HushEngine codebase, where we display the data of an entity’s components in the inspector, the asserts here establish two rules, for an entity to be shown in the inspector it needs to both, have a name, and a transform component, otherwise, something is very wrong about our assumptions at that point (the entity was probably not created properly because we forgot either component):

void Hush::InspectorPanel::RenderProperties()

{

Entity::Name* entityName = this->m_inspectTarget->GetComponent<Entity::Name>();

HUSH_ASSERT(entityName != nullptr, "Inspectable entities MUST have a name component!");

ImGui::SeparatorText(entityName->name.data());

LocalTransform *transform = this->m_inspectTarget->GetComponent<LocalTransform>();

HUSH_ASSERT(transform != nullptr, "Trying to render an entity without a Transform component!");

Serialize(transform);

}

This is an incredibly powerful pattern for catching bugs, and it has helped me a lot, preventing me from shipping code that will break in production, allowing it to break in development, this of course has to be complemented with extensive testing, but the general rule of thumb is to assert every assumption that you make, after all, they do get stripped in release mode, so you can be confident they won’t impact your code’s final performance.

”BUT WAIT, MY LANGUAGE DOES NOT HAVE ASSERTS!!”

I hear you yelling, well, worry not, most languages DO have exceptions, and we can leverage those to make up our own asserts, this is a very simple implementation I made in C# for a game jam that saved me hours of debugging.

public static class Assert {

public static void NotNull<T>(T? obj, string message = "") {

if (obj != null) return;

string errMsg = $"Assertion failed! {message}";

Log.Error(errMsg);

throw new System.Exception(errMsg);

}

public static void IsTrue(bool condition, string message = "") {

if (!condition) {

string errMsg = $"Assertion failed! {message}";

Log.Error(errMsg);

throw new System.Exception(errMsg);

}

}

}

It is stupidly simple, and has no business working as well as it does.

Assert usage on other languages

On a Movement script where physics are needed:

protected override void OnCreate() {

this.m_rig = this.GetComponent<RigidBodyComponent>();

Assert.NotNull(this.m_rig, "Rigidbody not found on entity, no movement can be applied!");

this.m_rig.AddTorque(SpartanMath.RandVec3(-1f, 1f).Normalized() * 3f);

this.m_dashCooldownTime = 0f;

this.m_state = EMovementState.Normal;

}

On a GameManager class, where all entities should be set in the inspector before playing the scene:

protected override void OnCreate() {

s_instance = this;

Assert.NotNull(player, "Player not set in manager!");

Assert.NotNull(playerBrightnessEntity, "Player brightness not set in manager!");

Assert.NotNull(this.PlayerBrightnessRef, "PlayerBrightness not found!");

Assert.NotNull(mainCam);

Assert.NotNull(this.environmentTray);

this.lightPickupMaterial.Emission = 5.0f;

this.GameOver = false;

this.m_lastSecond = 0;

this.PlayerBrightnessRef = this.playerBrightnessEntity.As<PlayerBrightness>();

this.MainCamera = mainCam.GetComponent<CameraComponent>();

this.EntitySpawnTray = this.environmentTray.As<EnvironmentTray>();

this.MovingTerrainRef = this.movingTerrain.As<MovingTerrain>();

this.m_gameOverText = this.GetComponent<TextComponent>();

this.m_replayText = this.replayTextEntity.GetComponent<TextComponent>();

}

Again, asserts are for DEBUG ONLY

One important caveat is that asserts will be stripped out in release builds, so, be sure to NEVER check user side data with them, for that we use runtime fail checks, which are essentially the same as an assert but they either do an early return or send an error message straight to the user.

Conclusion

So, what’s the takeaway here? Learning C is not about abandoning your favorite high-level language, nor is it about worshipping at the altar of pointers and manual memory management. It’s about stretching your brain in ways that abstractions never will. Just like tearing muscle fibers in the gym, the discomfort of dealing with raw data and defensive checks forces you to grow stronger as a programmer.

C teaches you to respect the machine, to anticipate failure, and to design with clarity. It strips away the safety nets and asks you to think about what your code is doing, why it’s doing it, and how it might break. And once you’ve wrestled with those fundamentals, every other language feels less like magic and more like a set of trade-offs you can consciously navigate.

For the next part, we’ll move into the territory that truly defines low-level programming: references and memory allocation.

We’ll talk about the decisions and sacrifices your favorite modern programming language makes to make it easier for you to think about logic, and how we can regain control a little bit and use the models given to us by C in other languages.